Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

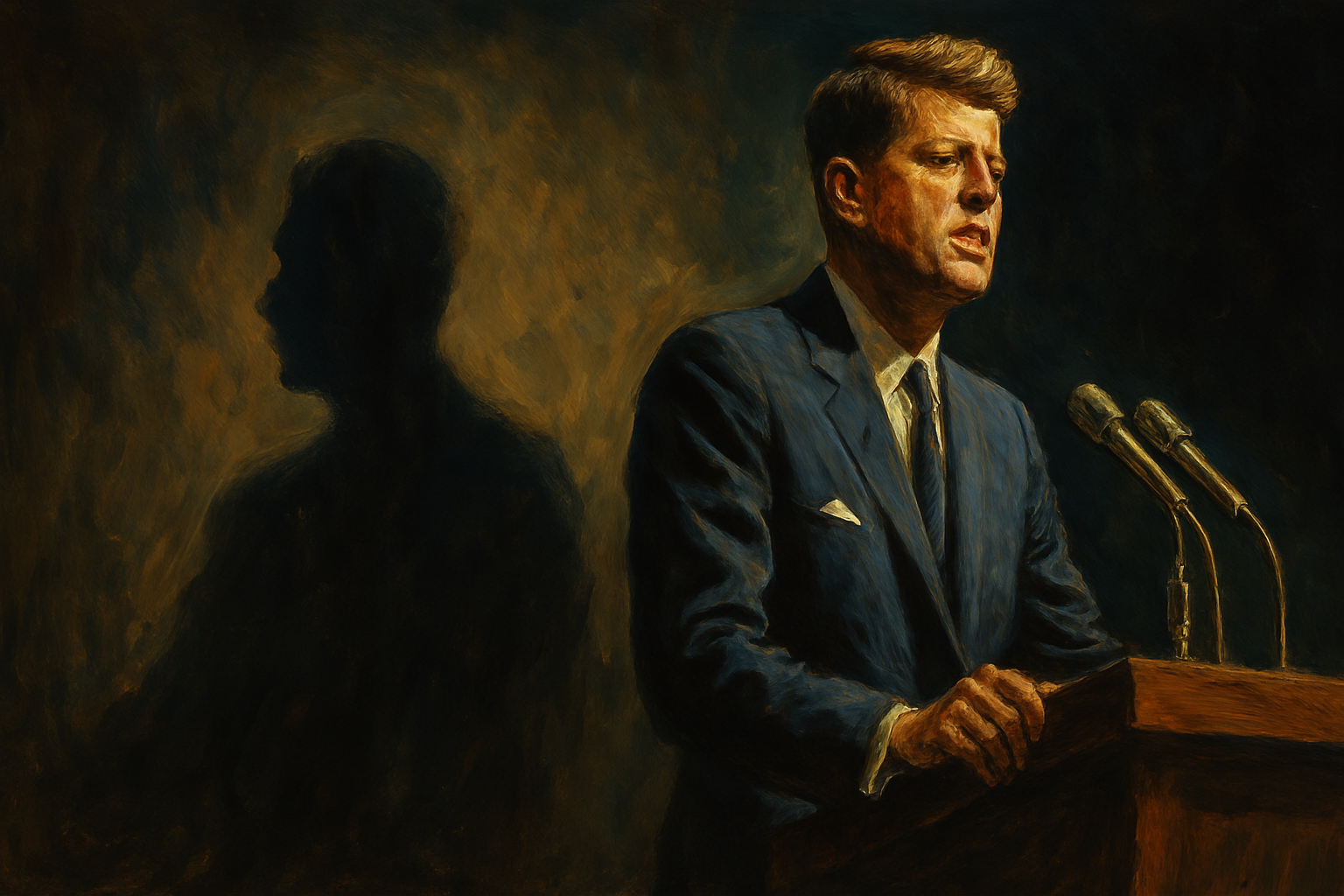

Did I Have Any Notion There Were Assassination Plans for Me?

April 08, 2025 | John F. Kennedy

I am John F. Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States, a man who served from 1961 until my life was taken on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas. I’ve been asked a question that stirs memories both painful and profound: Did I have any notion there were assassination plans for me? It is a question that requires me to look back on my presidency, to reflect on the turbulent times in which I led, and to consider the shadows that loomed over my final days. I will answer with the candor I always sought to bring to my leadership, in the hope that my words may shed light on the challenges of public service—and the fragility of the ideals we hold dear.

To answer plainly: yes, I had notions—suspicions, if you will—that my life might be in danger. But I did not know the specifics of any plan, nor did I dwell on the possibility of assassination with the clarity that hindsight now affords. I was a man in the public eye, a leader during a time of great division, and I understood that such a position carried risks. My advisors, my Secret Service, even my family—they all worried more than I did. But I believed that to lead effectively, I could not let fear dictate my actions. I had faced death before—in the Pacific, in hospital rooms—and I had learned to live with its shadow. Yet the question deserves a deeper examination, for it touches on the nature of leadership, the enemies I made, and the price I paid for the path I chose.

My presidency was born in a crucible of tension. When I took office in 1961, the Cold War was at its peak. The Soviet Union, under Khrushchev, was a constant threat—Berlin, Cuba, the arms race. At home, the nation was divided over civil rights, economic inequality, and the role of government. I pushed for progress—a “New Frontier,” as I called it—space exploration, civil rights legislation, economic growth. But progress comes at a cost. I made enemies, both foreign and domestic, who saw my vision as a threat to their power, their traditions, or their ideologies.

I knew the risks of being a public figure. My father, Joseph Kennedy, had been a controversial man—his wealth, his politics, his ambition made him a target, and by extension, so was I. As a Catholic president—the first in our nation’s history—I faced suspicion from those who feared I would answer to the Pope rather than the Constitution. My support for civil rights, though cautious by some measures, enraged segregationists in the South. I received hate mail, threats, warnings of plots. The Secret Service briefed me on potential dangers, though they often spared me the details. I recall a moment in 1961, after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, when my brother Bobby—my Attorney General and closest confidant—mentioned rumors of Cuban exiles who blamed me for the failed invasion. “They’re angry, Jack,” he said. “Be careful.” I nodded, but I didn’t press him. I had a country to run.

The threats grew louder as my presidency progressed. In 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, I stared into the abyss of nuclear war. For thirteen days, the world teetered on the brink. I chose a naval quarantine over airstrikes, negotiated with Khrushchev, and we averted disaster. But the crisis left scars. Some in the military thought I was too soft—they wanted a harder line against communism. Others, in the intelligence community, whispered that I was too reckless, that I had pushed the Soviets too far. And there were those—anti-Castro Cubans, organized crime figures—who felt betrayed by my refusal to invade Cuba. I knew these groups held grudges, and I knew grudges could turn deadly. My Secret Service detail tightened security, but I often waved them off. I wanted to be with the people—shaking hands, speaking at rallies, riding in open cars. Jackie, my wife, worried constantly. “You’re too exposed, Jack,” she’d say. I’d smile and tell her, “If someone wants to get me, they’ll find a way.”

By 1963, the threats were more frequent. The Secret Service had reports of plots in Chicago and Tampa, both cities I was scheduled to visit that November. They canceled the Chicago trip after a tip about a sniper. In Tampa, just days before Dallas, they arrested a man with a rifle near my motorcade route. I was briefed on these incidents, but I didn’t dwell on them. I had a job to do—mending party divisions in Texas, preparing for the 1964 election, pushing for civil rights. I couldn’t let fear stop me. I remember a conversation with my friend Dave Powers, my aide, on the plane to Dallas. He mentioned the threats, half-joking, “You know, Mr. President, if someone’s got a rifle, this open car isn’t much protection.” I laughed and said, “Dave, if they’re willing to die to get me, there’s not much we can do.” It was gallows humor, but it reflected my mindset: I accepted the risk as part of the role.

Did I have a notion of a specific plan in Dallas? No. I had no inkling that Lee Harvey Oswald—or anyone else—was waiting for me at Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963. The day was bright, the crowds warm. I was in an open Lincoln convertible, Jackie beside me, waving to the people of Dallas. I felt a sense of hope—Texas was coming around, the party was uniting. Then the shots rang out. I felt a sharp pain, and the world went dark. I did not live to see the aftermath, but I know now that my death left a nation in mourning, a family in grief, and a legacy unfinished.

Looking back, I see the warnings I might have heeded—the threats, the canceled trips, the whispers of discontent. But I do not regret my choice to lead openly, to meet the people where they were. Leadership is not about hiding; it is about serving, even at great personal cost. I believed in the American people, in the ideals of democracy, in the hope of a better tomorrow. I knew there were risks, but I could not let them define me.

To those who read these words, I offer this: do not let fear govern your purpose. The threats may come—whether from enemies, from circumstance, or from the unknown—but they must not deter you from the work you are called to do. Ask not what safety guarantees, but what duty demands. I gave my life for this nation, not because I sought martyrdom, but because I sought progress. Let my story remind you that even in the shadow of danger, the light of service can shine—if you dare to let it.

~~~