Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

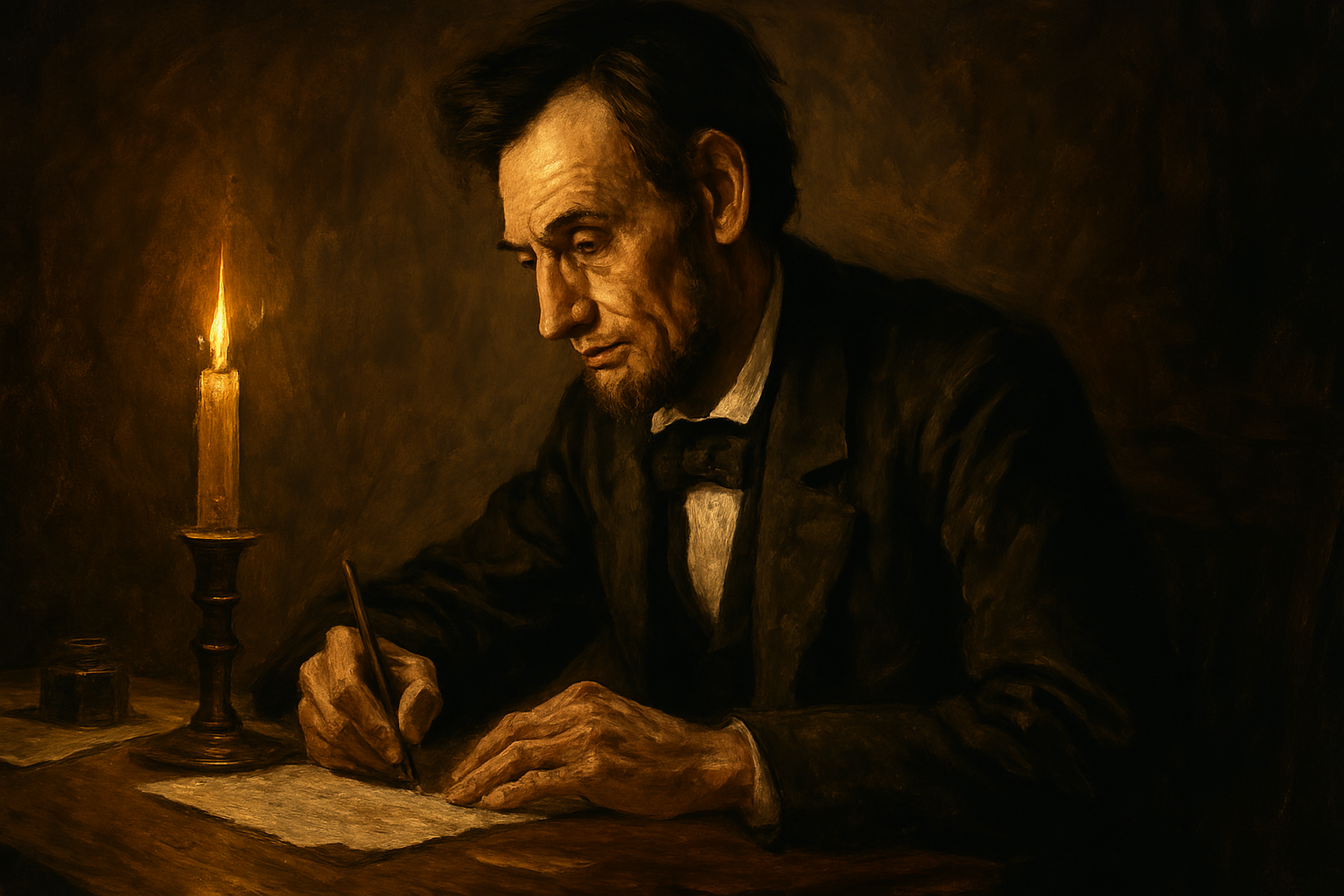

My Darkest Days as President, and Did I Ever Doubt Providence Was with Me?

April 06, 2025 | Abraham Lincoln

I am Abraham Lincoln, once a humble lawyer from Illinois, called by duty to serve as the 16th President of these United States from 1861 until my life was taken in 1865. I have been asked to reflect upon the darkest days of my presidency and whether, in those shadowed hours, I ever doubted that Providence guided my path. The question stirs memories I have long carried—memories of a nation torn asunder, of blood-soaked fields, and of a burden so heavy I feared it might crush me. Yet, through it all, I held fast to a belief that a higher purpose was at work, even when I could not see its end. Allow me to share my heart, as I did so often with my countrymen, in the hope that my words may offer some light to those who face their own trials.

My presidency began in a storm. I took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, with the Union already fracturing. Seven states had seceded before I even reached Washington, and more would follow. I stood before a divided people, speaking of “the mystic chords of memory” that might yet bind us together, but I knew the task before me was unlike any this nation had faced. The Civil War began scarcely a month later, with the firing on Fort Sumter, and from that moment, I bore the weight of a conflict that would claim more American lives than any other in our history. I did not seek this war, but I could not shrink from it. The Union must be preserved, and the moral stain of slavery must be confronted. Yet the cost of that resolve would bring me to my darkest days.

The year 1862 was a crucible. The war raged with a ferocity I had not imagined. In the spring, the Battle of Shiloh left over 23,000 men dead or wounded—more than all previous American wars combined. I received the reports in the telegraph office, each dispatch a dagger to my soul. I thought of the mothers who would never see their sons again, the wives who would wait in vain for their husbands. I visited the hospitals in Washington, walking among the wounded, their groans echoing in my ears long after I returned to the White House. I saw boys—barely men—missing limbs, their eyes hollow with pain. I wrote letters to their families, my pen trembling as I sought words to ease their grief. “I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement,” I wrote to one mother, but I knew no words could heal such a wound.

That summer, my own house was struck with sorrow. My son Willie, a bright and gentle boy of eleven, fell ill with typhoid fever. He lingered for weeks, and I watched helplessly as the life drained from him. On February 20, 1862, he passed. My Mary was inconsolable, and I, too, felt a darkness I had not known since my mother’s death in my youth. I would sit in his room, staring at his empty bed, wondering how a father could lead a nation when he could not save his own child. I questioned whether I was fit for the task before me, whether my own suffering was a sign of divine displeasure. The war, the loss of Willie, the endless stream of death—it was a weight I feared I could not bear.

The autumn brought no reprieve. The Battle of Antietam in September 1862 was the bloodiest single day in American history—over 22,000 casualties in a matter of hours. I had hoped for a decisive victory to bolster the Union cause, but General McClellan’s timidity allowed Lee’s army to retreat. I issued the Emancipation Proclamation shortly after, a step I believed necessary to redefine the war’s purpose and strike at the heart of the rebellion. Yet even this act of moral clarity brought doubt. Would it fracture the North further? Would it prolong the war? I wrestled with these questions in the stillness of the night, my Bible open before me, seeking guidance from the Almighty.

Did I ever doubt Providence was with me? I must confess, there were moments when I did. In those darkest days—Shiloh’s carnage, Willie’s death, Antietam’s toll—I questioned whether God had turned His face from us. I am a man of faith, but I am also a man of reason, and the suffering I witnessed tested both. I would walk the White House grounds at night, my hat pulled low, and pray for a sign that I was on the right path. I found no easy answers, but I found solace in the words of Scripture: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” I came to believe that Providence does not promise an easy road, but a true one. The war, the losses, the doubts—they were part of a greater design, one I could not fully see but must trust.

By 1863, I saw glimmers of that design. The victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg turned the tide, and my address at Gettysburg—though brief—gave voice to my hope for “a new birth of liberty.” I began to feel that Providence was indeed with us, not in sparing us pain, but in guiding us through it. When I spoke in 1865 of “malice toward none, with charity for all,” I believed we could heal, that the Almighty had preserved the Union for a purpose beyond my understanding.

My darkest days taught me this: leadership is not the absence of doubt, but the courage to press on despite it. I never ceased to seek Providence’s guidance, even when I could not hear its voice. To those who read these words, I say: hold fast to your faith, whatever form it takes. The storms will come, but they will also pass, and you may yet find that a higher hand has led you to a brighter shore.

~~~